October 16, 1967 - The Jungle Book

Have you ever seen Richard Williams' The Thief and the Cobbler? And by that I mean the fuller, unexpurgated versions floating around online, not the dreadful dub n' hack version released by Disney.

It's a fascinating film, not least of which because Williams refused to storyboard the film. As a result, each shot in a sequence is as long as its' animator wished it to be. As a result, each shot has internal rhythms but the larger sequences do not, dictated as they are by such factors as speed, fatigue, and interest. It's an animator's dream but an editor's nightmare.

I think Thief and the Cobbler helps illustrate why the 60s and 70s Disney animated features are so pokily paced. Through the 50s, Walt and others insisted on keeping the pace up and the narrative tight, but as animators like Ollie Johnston and Ken Anderson were given more latitude to craft sequences, the whole pace of the enterprise slows down to a casual wobble. It's the pace of animation allowed to exist for its own sake.

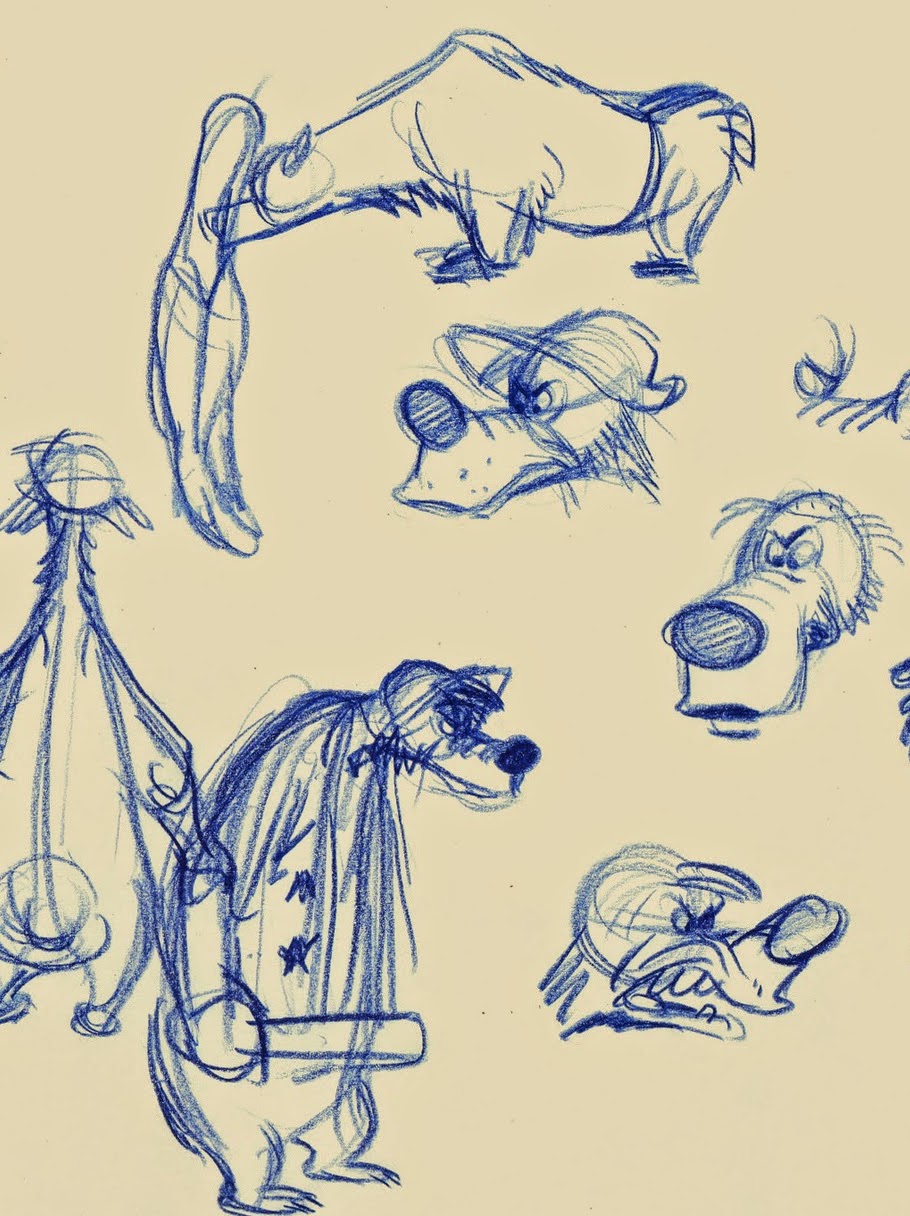

The Jungle Book is the ultimate Disney clip show movie. It's the first Disney film I'd be comfortable calling a road movie - while an argument can be mounted for Pinocchio, it's Jungle Book that sticks pretty closely to the road movie formula. The frame story is a linear movement from point A to point B, and each "stop" along the way is a self-contained episode that can be split off from the other episodes with little lost. Within those episodes, the animation is astonishing, and with the slacker pace and structure in place it's the animated performances that totally drive the film. That's a good thing, because the road movie formula thrives on vivid characters and incidents, allowing us to project ourselves into these situations through central characters on a journey who are no more than ciphers.

Honestly, if there's a problem with Jungle Book, it's Mowgli the man-cub. While he's cute enough, Mowgli is a big donut-hole in a film filled with remarkable personalities. He's voiced by director Reitherman's son Bruce, who does a serviceable job and provides some live-action reference that will be animated and recycled as Christopher Robin in The Many Adventures of Winnie-the-Pooh. Disney's Mowgli is a far cry from the fierce and wise survivor of Ripling's book or the 1942 film. When he's about to be mauled by Shere Khan we express only minor alarm. When he's about to be devoured by Kaa we register amusement. This makes the Jungle Book a weirdly passive experience: even Baloo steals all of the big emotional moments. In the final reel, as Mowgli vanishes into the human village, we shrug in amusement the same way Bagheera does and the film returns, much more deservedly, to Baloo and Bagheera as they saunter off into the sunset.

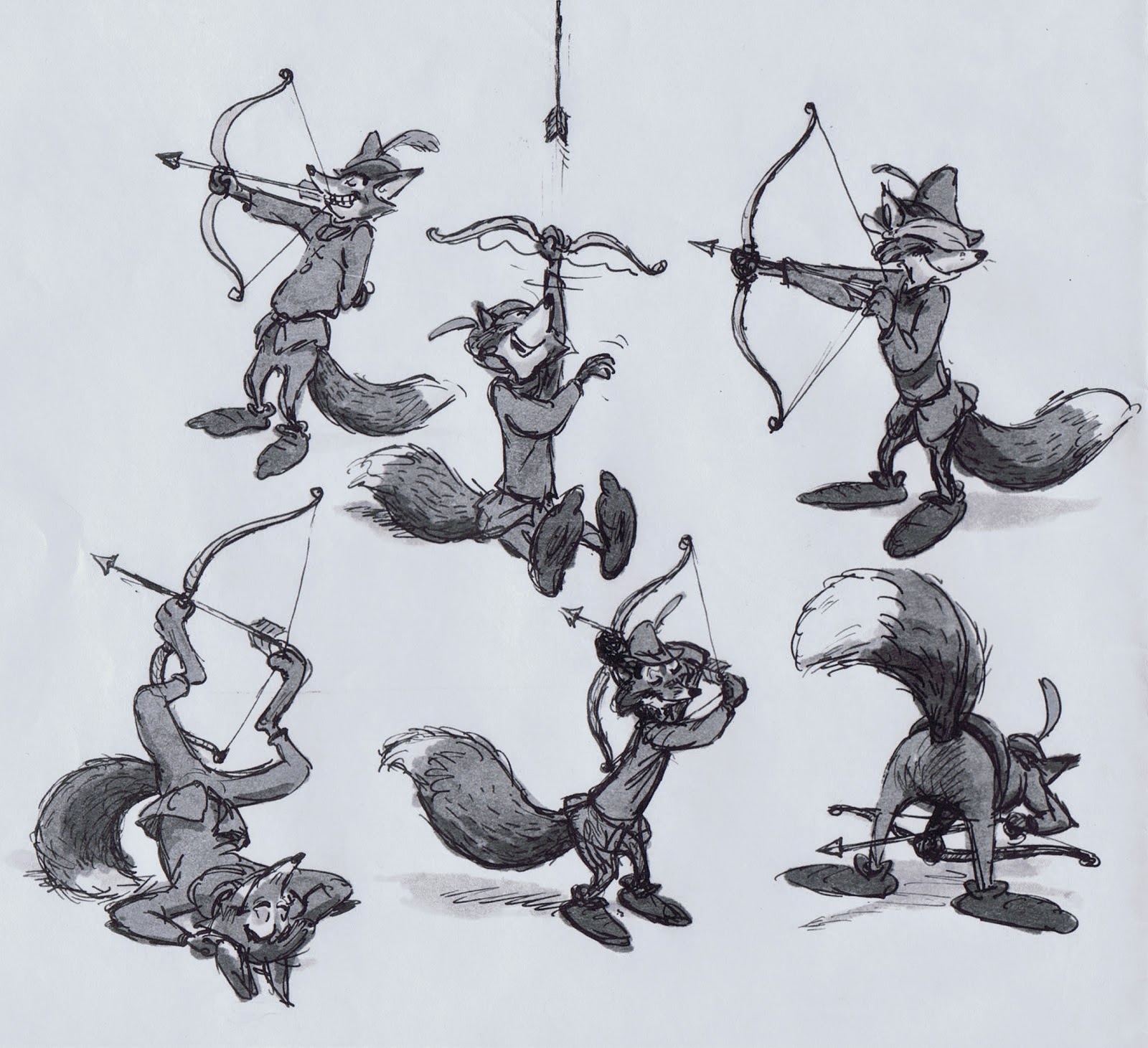

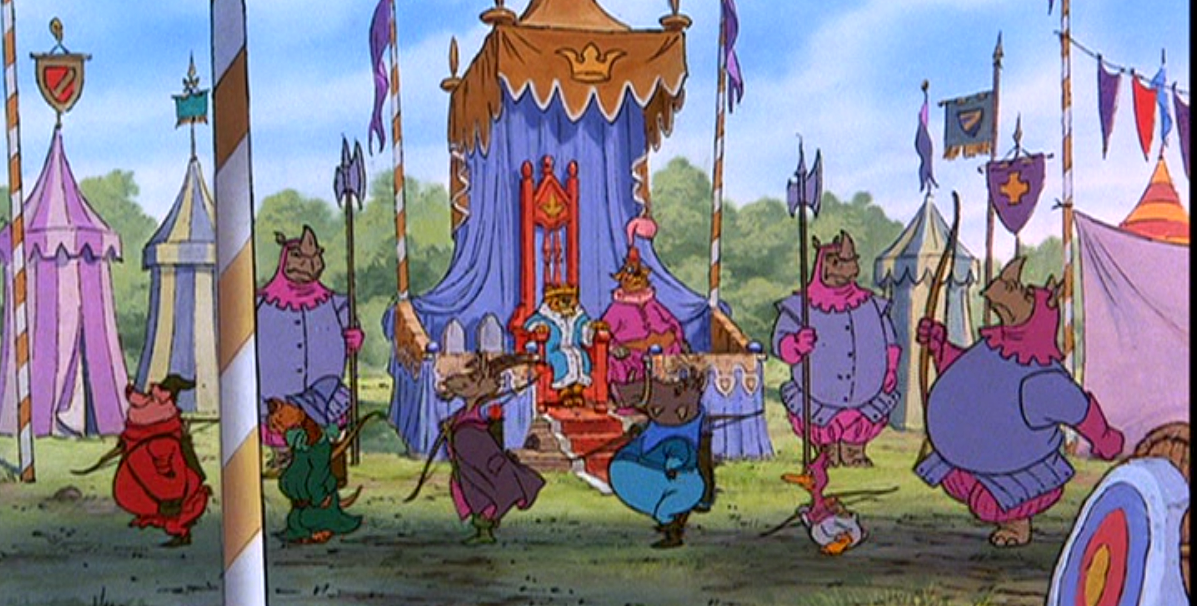

What separates Jungle Book from atmospheric but dramatically inert rambles like Sword in the Stone or Robin Hood is probably what Walt brought, which is a fastidious attention to structure and rhythm. Each sequence has a big bit of slapstick action or a clever song or, often enough, both. There are two sets of two characters, with Mowgli standing between each: Bagheera and Baloo complement Kaa and Shere Khan. Each of these four characters have two big scenes, one in each half of the movie. The entire film is bisected by King Louie, who can only appear once for danger of stealing the whole show. Louie himself is a comic figure who becomes increasingly sinister as his sequence unfolds, paving the way for the sinister Shere Khan who is lightened by touches of comedy.

This is a really nicely set up film which requires the animators knock down the sequences, neatly and cleanly; in other words Walt constructed the only film which truly plays to the strengths of the animation unit in the Reitherman era.

The film slacks in the last few reels where it really should be getting tighter; the Beatle-vultures who sing "That's What Friends Are For" are funny enough but the scene wouldn't be harmed by removing them and proceeding directly to the confrontation with Khan. It's a shame that John, George, Paul and Ringo turned these roles down, for no other reason than it'd perk up a scene in need of perking. On the other hand, the roles seem to reflect the public image of the Beatles as ludicrous mop-topped good natured slackers, an image the Beatles themselves had been working to escape for the better part of two years at the time of Jungle Book's release. The disconnect between the sophistication of the actual Beatles act, which in October 1967 was between Srgt. Pepper and the "White Album", and this fun-house reflection by Disney, the squarest of the square studios, is deliciously inappropriate. Or is the casting of the bandleaders of the psychedelic movement as scavenging birds a subtle slam?

Watching Jungle Book I was reminded of a piquant passage in Walter Kerr's The Silent Clowns where Kerr describes the poetic effect of the best silent performances. Silent films were shot in cameras cranked by hand and projected back at a pace rate somewhere around 20 fps, you see, and since the human hand is not a motor there is naturally a subtle, almost organic fluctuation in the rate at which the image is exposed. When you project this back at the right speed the result is a slight increase in the movement of the human onscreen. Turns become balletic, falls become spectacular, and the very best of the silent stars - Lon Chaney, Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Harold Lloyd, Charlie Chaplin - could modulate their movements onscreen to look remarkably graceful on playback. It's not the way people move - it's better.

Great animation is a lot like that. These animals are more human than people can be. They move, think, react better, faster, funnier than people do. That's why when we see sped-up human actors bouncing around in, say, the Gnome-Mobile the effect is the opposite of what's intended... ghoulish and artificial, the opposite of being magical and effortless. It's just people moving twice as fast, not twice as well. You have to go to the Disney animated films to get the real deal.

Still, from the gorgeously painted backdrops to George Bruns' haunting score, I prefer Jungle Book to the roughly similar Lion King. Walt's road movie may not express the full breadth of his brilliance, but it shows America's last great showman as the last great coordinator of the craft he helped create.

October 16, 1967 - Charlie, the Lonesome Cougar

Okay, who here has heard of Lev Kuleshov? If you have, then you know where this is going.

Kuleshov was an early film experimenter who devised a simple series of shots which wrote his name in history. The shots were images of a bowl of soup, a little girl in a coffin, and the woman reclining on a couch. Each shot was edited together with a repeated shot of an actor staring impassively into the camera. When this actor's blank face was contextualized by the soup, the dead girl, etc, audiences experienced through the actor the idea of hunger, grief, or love.

Kuleshov was not the first person to figure this out. In Hollywood, filmmakers had been experimenting for years with editing - in the service of storytelling. American directors found that they could cut together two strips of film to give the illusion of continuous action - a pioneer family trapped by Indians as the Calvary rides to their rescue, for example - to create dramatic effects. Editing could also be used for purely spatial effects - Charlie Chaplin walks off frame right and enters frame left in the next shot and we know he is in the next room over. As basic as all this is, there was a time when these were radical ideas.

The "Kuleshov Effect" is basically the big thing Charlie has going for it. As entertainment it's modest - unless you are a filmmaker or editor, in which case it becomes fairly interesting. Trained cougars flounce around nondescript shacks or cross logs and the magic of editing makes them into an endearing character: Good-Time Charlie, the cougar kitten of the pacific northwest.

This film has a disarming gravitas because it appears to be what it manifestly is not: a documentary. Shot in grainy 16mm on what appears to be a wing and a prayer, Charlie inter cuts trained cougars, actors, non-actors, and documentary material into a surprising whole. Were the result a bit more demanding on the audience, it could qualify as avant-garde. As it is the film has the squirmy, uncomfortable sense of is-it-real-or-not captured in films like The Blair Witch Project or Boggy Creek II.

Casually narrated by Rex Allen, and with a uniquely terrible theme song, Charlie is a B movie release all the way, but it's not all that bad. Demanding only about an hour of your life, even the poky pace and mediocre actors give a sense of weight to the basic illusion of the film. Looking back at it from 2014, it's remarkable that this film even qualified for a theatrical release by a major studio - a lot of what can be found on YouTube looks more professional.

The film appears to have been shot mostly or entirely silent on location; actors are looped shouting dialogue while onscreen in Washington are seen gesturing wildly. Close ups and dialogue points that move the story forward were shot back in Burbank on the optical stage; these shots stand out because the actors are sharp and synchronized while the background is soft and grainy. One shot of actor Ron Brown did not have the background optically inserted so he momentarily appears to stand in a black void; this was left in the movie! One wonders if the whole thing was just made up as they went along. It's more of a fascinating byproduct of an unusual creative process than it is an honestly good movie.

Still, it's cute enough. I wonder if the kids ran around the theater the whole time Roger Ebert saw it.

November 30, 1967 - The Happiest Millionaire

"I understand Mr. Biddle is going off to war."

"I'm glad to hear it. Maybe we'll finally have some peace around here."

Well, here it is, and at least it's out of the way early - the longest official Disney movie.

If we're talking about Disney movies as things Walt Disney personally oversaw, Happiest Millionaire is pretty much the end of the line. For Disney people, it's an item of particular fascination, because of what it is and also what it isn't. Walt's hand is felt very strongly in this one, but so is his absence.

What we really need to begin with here is addressing why this is a Disney movie at all. One of the most consistent claims for the true top tier classics is that Disney films are timeless - and whether that's true or not, what a "Disney Movie" is is a distinct enough sub genre that those films which fit pretty well into it and remain in the consciousness tend to keep getting watched. Despite being as of it's era (ie 1938) as something like Mr. Moto's Gamble, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs also works well enough as a "Disney movie" that people are still watching it, 80 years later.

Happiest Millionaire isn't one of those. There's no fairy tale element, no magic, no scary villain. There isn't really even a neat moral like "love conquers all" or "families are magical" or whatever it is that Mary Poppins is about. In fact, looking back from today it may not even be obvious why Disney made it at all. Outside of the context of 1964, it's hard to see Mary Poppins as part of a string of high-budget color musicals which began officially with Gigi in 1958. Poppins itself was up against My Fair Lady for best picture of 1964, and the prestige musical cycle continued into the 1970s. In 1968, the year that the landmark 2001 was in theaters, the best picture winner was... Oliver. A fine film, sure, but best picture?

There was money and prestige to be had in this sort of thing, however, and so Happiest Millionaire went from a minor stage comedy to an expensive musical. Walt spared no expense: a talented cast, hugely elaborate sets furnished with real antiques, and a full overture, intermission, and exit music - Millionaire was an A-picture effort. Fans of 1960s musicals are more likely to get something out of it than other viewers.

It's doubly unfortunate, then, that Walt died shortly after the first cut (ie, a rough assembly) was made. In its full form, Millionaire is an absurdly, butt-numbingly long movie. The Shermans here contribute three great songs and a bunch of just okay ones, and their music all but vanishes from a long stretch of the second half.

Millionaire is a film that defines the concept of "bloated". An introductory number - which fades up out of a painting, the exact same gag used to start Bullwhip Griffin - is lots of fun but takes forever to get actor Tommy Steele to the actual mansion where the film will take place. There's at least five gags along the way that stop the momentum and once he gets there he dances up and down the front steps to sing his final refrain. This would be fine by itself but the entire film has this same everything-but-the-kitchen-sink mentality. Once Steele gets into the mansion, two brothers who never re-appear sing a song to demonstrate the family affinity for boxing and knock out their sister's suitor, who also never re-appears. Later, sister Cordelia has her roommate teach her how to dance in the current fashionable way in a tedious musical sequence. When Cordelia gets to the dance she hardly even uses her new moves and is swept off her feet in yet another song about dancing.

Tommy Steele, as butler John Lawless, sings and grins up a storm and steals the show, although to be fair he doesn't have too much competition. Fred MacMurray is surprisingly good here, and demonstrates a nice singing voice from time to time. Greer Garson as his wife is mostly on view to stand around and scold him; their most effective scene comes at the very end of the film and was cut from all theatrical prints. Gladys Cooper is the only real competition for Steele; her dressing down of Geraldine Paige is the highlight of the second half. MacMurray keeps alligators in his conservatory because... well, that doesn't really go anywhere either, except to provide a slapstick sequence at the 90 minute mark which, typically, goes on about ten minutes too long. Near the end there's another slapstick sequence in a bar with a terrific Shermans song, Let's Have A Drink On It, that would play better if we hadn't been beaten down to the point of apathy by two and a half hours of go-nowhere material preceding it.

The real problem is that Millionaire has no real sense of how to condense all of this into something better than its constituent parts. Details aren't just redundant, they're absurdly redundant. Even the best musical numbers are too long. Characters drift in and out randomly without any reason to be there. Each plot point is treated with about the same dramatic emphasis as everything else, as if Cordelia going off to boarding school requires the same dramatic weight as her deciding to get married.

This is a shame because what works in the movie is really good. Even MacMurray, who comes off somewhat dry in other similar roles for Disney, is unexpectedly moving when he's finally faced with an empty nest. Then, of course, he ends up going off to World War I.

Oh yes, I haven't even mentioned that the film is set between 1914 and 1917. The period atmosphere is nicely handled, with a pleasing emphasis on vintage publications like the New York Times, Saturday Evening Post, Town and Country and Harper's Bazaar. MacMuray as Biddle has extended dealings with the Marines after being kicked out of every office in Washington. He knocks out their best boxer and so the corp tolerates his efforts to teach them "self defense".

These are more scenes that do very little to advance the plot, and sadly that's about where the period detail ends. Either director Norman Tokar or cinematographer Edward Colman decided to shoot everything bright, wide, and flat, like a TV movie. It looks like every set was lit exactly once and the power switch was thrown at the start of shooting each day with no extra emphasis. It's almost impossible to tell day scenes from night scenes. Outside of a few matte paintings, there's no sense of the Biddle house as a real place. MacMurray is supposed to have a converted garage out back that he

teaches his bible/boxing classes in, but you have to watch the film a few times to understand how this connects to and relates to the house; it's just another set. When you consider the atmosphere a director like Robert Stevenson brought to even the weakest Disney movies he was handed, this is another huge demerit to this film.

Then there's the central romance between Cordelia Biddle and Angier Duke. Probably the only onscreen romance between a boxing tomboy and a jiu jitsu-tossing car enthusiast (this plot point is exceptionally weird), actors Lesie Ann Warren and John Davidson do a perfectly straightforward good job. Davidson's big ballad about Detroit, where he longs to move and become an automobile magnate, isn't very good but Davidson sells his dream well. Weirdly, the actual sequence of Davidson singing his love song to Detroit is the only one staged in the countryside - the natural trees and open sky contrasted directly with his lyrics about "a land where golden chariots are molded out of dreams". When Cordelia agrees to move with him to Detroit, the heavens open up into a menacing rainstorm. The shot proceeding it is eerily like the roadside confession in Vertigo. Is this a premonition?

The last shot of the film is an unexpected downer - Cordelia and Angie's car rolling towards a hell scape city skyline belching smoke. It's like something out of a horror movie and ends the film on an uncomfortable note - are we supposed to find this as appalling as it looks? If so, then how are we supposed to feel about this romance?

I'm sounding really down on this movie, and I shouldn't, because despite all of its problems I do like it. But it's very much a film that appears as if it could have cohered into a minor classic had there been a mediating influence like Walt Disney to iron out the problems and insist on keeping the pace up. This is almost a film that demands its own fan edit, like others have done with Star Wars.

In many ways this film seems to have been orphaned by Disney. The DVD release, in non-anamorphic widescreen, is bleary and pixellated. There are no extras to provide much needed background and context. In this form, even the visual and textual pleasure of the film are too blurred to really enjoy. As unlikely as it may be, this film would really benefit from a HD upgrade.

I didn't really expect to watch Millionaire all the way through again for this review, having seen it several times before, but once the film started unrolling I found myself watching it and enjoying it and it mostly held my attention, so despite the hundreds of words of misgivings I've typed up above, there is something to it that I find worthwhile. This one is recommended to interested parties who know what they're getting into. Ordinarily I'd say a product like this is a ruin of a great film, but that assumes that the film was ever built to completion to begin with, which it wasn't. The Happiest Millionaire is more like a pallet of lumber that's supposed to be a house. You supply the nails.

For next week: Blackbeard's Ghost, The One and Only Genuine Original Family Band, and Never A Dull Moment

Have you ever seen Richard Williams' The Thief and the Cobbler? And by that I mean the fuller, unexpurgated versions floating around online, not the dreadful dub n' hack version released by Disney.

It's a fascinating film, not least of which because Williams refused to storyboard the film. As a result, each shot in a sequence is as long as its' animator wished it to be. As a result, each shot has internal rhythms but the larger sequences do not, dictated as they are by such factors as speed, fatigue, and interest. It's an animator's dream but an editor's nightmare.

I think Thief and the Cobbler helps illustrate why the 60s and 70s Disney animated features are so pokily paced. Through the 50s, Walt and others insisted on keeping the pace up and the narrative tight, but as animators like Ollie Johnston and Ken Anderson were given more latitude to craft sequences, the whole pace of the enterprise slows down to a casual wobble. It's the pace of animation allowed to exist for its own sake.

The Jungle Book is the ultimate Disney clip show movie. It's the first Disney film I'd be comfortable calling a road movie - while an argument can be mounted for Pinocchio, it's Jungle Book that sticks pretty closely to the road movie formula. The frame story is a linear movement from point A to point B, and each "stop" along the way is a self-contained episode that can be split off from the other episodes with little lost. Within those episodes, the animation is astonishing, and with the slacker pace and structure in place it's the animated performances that totally drive the film. That's a good thing, because the road movie formula thrives on vivid characters and incidents, allowing us to project ourselves into these situations through central characters on a journey who are no more than ciphers.

|

| a pivotal scene. |

What separates Jungle Book from atmospheric but dramatically inert rambles like Sword in the Stone or Robin Hood is probably what Walt brought, which is a fastidious attention to structure and rhythm. Each sequence has a big bit of slapstick action or a clever song or, often enough, both. There are two sets of two characters, with Mowgli standing between each: Bagheera and Baloo complement Kaa and Shere Khan. Each of these four characters have two big scenes, one in each half of the movie. The entire film is bisected by King Louie, who can only appear once for danger of stealing the whole show. Louie himself is a comic figure who becomes increasingly sinister as his sequence unfolds, paving the way for the sinister Shere Khan who is lightened by touches of comedy.

This is a really nicely set up film which requires the animators knock down the sequences, neatly and cleanly; in other words Walt constructed the only film which truly plays to the strengths of the animation unit in the Reitherman era.

The film slacks in the last few reels where it really should be getting tighter; the Beatle-vultures who sing "That's What Friends Are For" are funny enough but the scene wouldn't be harmed by removing them and proceeding directly to the confrontation with Khan. It's a shame that John, George, Paul and Ringo turned these roles down, for no other reason than it'd perk up a scene in need of perking. On the other hand, the roles seem to reflect the public image of the Beatles as ludicrous mop-topped good natured slackers, an image the Beatles themselves had been working to escape for the better part of two years at the time of Jungle Book's release. The disconnect between the sophistication of the actual Beatles act, which in October 1967 was between Srgt. Pepper and the "White Album", and this fun-house reflection by Disney, the squarest of the square studios, is deliciously inappropriate. Or is the casting of the bandleaders of the psychedelic movement as scavenging birds a subtle slam?

Watching Jungle Book I was reminded of a piquant passage in Walter Kerr's The Silent Clowns where Kerr describes the poetic effect of the best silent performances. Silent films were shot in cameras cranked by hand and projected back at a pace rate somewhere around 20 fps, you see, and since the human hand is not a motor there is naturally a subtle, almost organic fluctuation in the rate at which the image is exposed. When you project this back at the right speed the result is a slight increase in the movement of the human onscreen. Turns become balletic, falls become spectacular, and the very best of the silent stars - Lon Chaney, Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Harold Lloyd, Charlie Chaplin - could modulate their movements onscreen to look remarkably graceful on playback. It's not the way people move - it's better.

Great animation is a lot like that. These animals are more human than people can be. They move, think, react better, faster, funnier than people do. That's why when we see sped-up human actors bouncing around in, say, the Gnome-Mobile the effect is the opposite of what's intended... ghoulish and artificial, the opposite of being magical and effortless. It's just people moving twice as fast, not twice as well. You have to go to the Disney animated films to get the real deal.

Still, from the gorgeously painted backdrops to George Bruns' haunting score, I prefer Jungle Book to the roughly similar Lion King. Walt's road movie may not express the full breadth of his brilliance, but it shows America's last great showman as the last great coordinator of the craft he helped create.

October 16, 1967 - Charlie, the Lonesome Cougar

Okay, who here has heard of Lev Kuleshov? If you have, then you know where this is going.

Kuleshov was an early film experimenter who devised a simple series of shots which wrote his name in history. The shots were images of a bowl of soup, a little girl in a coffin, and the woman reclining on a couch. Each shot was edited together with a repeated shot of an actor staring impassively into the camera. When this actor's blank face was contextualized by the soup, the dead girl, etc, audiences experienced through the actor the idea of hunger, grief, or love.

Kuleshov was not the first person to figure this out. In Hollywood, filmmakers had been experimenting for years with editing - in the service of storytelling. American directors found that they could cut together two strips of film to give the illusion of continuous action - a pioneer family trapped by Indians as the Calvary rides to their rescue, for example - to create dramatic effects. Editing could also be used for purely spatial effects - Charlie Chaplin walks off frame right and enters frame left in the next shot and we know he is in the next room over. As basic as all this is, there was a time when these were radical ideas.

The "Kuleshov Effect" is basically the big thing Charlie has going for it. As entertainment it's modest - unless you are a filmmaker or editor, in which case it becomes fairly interesting. Trained cougars flounce around nondescript shacks or cross logs and the magic of editing makes them into an endearing character: Good-Time Charlie, the cougar kitten of the pacific northwest.

|

| "I'm acting!" |

Casually narrated by Rex Allen, and with a uniquely terrible theme song, Charlie is a B movie release all the way, but it's not all that bad. Demanding only about an hour of your life, even the poky pace and mediocre actors give a sense of weight to the basic illusion of the film. Looking back at it from 2014, it's remarkable that this film even qualified for a theatrical release by a major studio - a lot of what can be found on YouTube looks more professional.

The film appears to have been shot mostly or entirely silent on location; actors are looped shouting dialogue while onscreen in Washington are seen gesturing wildly. Close ups and dialogue points that move the story forward were shot back in Burbank on the optical stage; these shots stand out because the actors are sharp and synchronized while the background is soft and grainy. One shot of actor Ron Brown did not have the background optically inserted so he momentarily appears to stand in a black void; this was left in the movie! One wonders if the whole thing was just made up as they went along. It's more of a fascinating byproduct of an unusual creative process than it is an honestly good movie.

Still, it's cute enough. I wonder if the kids ran around the theater the whole time Roger Ebert saw it.

November 30, 1967 - The Happiest Millionaire

"I understand Mr. Biddle is going off to war."

"I'm glad to hear it. Maybe we'll finally have some peace around here."

Well, here it is, and at least it's out of the way early - the longest official Disney movie.

If we're talking about Disney movies as things Walt Disney personally oversaw, Happiest Millionaire is pretty much the end of the line. For Disney people, it's an item of particular fascination, because of what it is and also what it isn't. Walt's hand is felt very strongly in this one, but so is his absence.

What we really need to begin with here is addressing why this is a Disney movie at all. One of the most consistent claims for the true top tier classics is that Disney films are timeless - and whether that's true or not, what a "Disney Movie" is is a distinct enough sub genre that those films which fit pretty well into it and remain in the consciousness tend to keep getting watched. Despite being as of it's era (ie 1938) as something like Mr. Moto's Gamble, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs also works well enough as a "Disney movie" that people are still watching it, 80 years later.

Happiest Millionaire isn't one of those. There's no fairy tale element, no magic, no scary villain. There isn't really even a neat moral like "love conquers all" or "families are magical" or whatever it is that Mary Poppins is about. In fact, looking back from today it may not even be obvious why Disney made it at all. Outside of the context of 1964, it's hard to see Mary Poppins as part of a string of high-budget color musicals which began officially with Gigi in 1958. Poppins itself was up against My Fair Lady for best picture of 1964, and the prestige musical cycle continued into the 1970s. In 1968, the year that the landmark 2001 was in theaters, the best picture winner was... Oliver. A fine film, sure, but best picture?

There was money and prestige to be had in this sort of thing, however, and so Happiest Millionaire went from a minor stage comedy to an expensive musical. Walt spared no expense: a talented cast, hugely elaborate sets furnished with real antiques, and a full overture, intermission, and exit music - Millionaire was an A-picture effort. Fans of 1960s musicals are more likely to get something out of it than other viewers.

It's doubly unfortunate, then, that Walt died shortly after the first cut (ie, a rough assembly) was made. In its full form, Millionaire is an absurdly, butt-numbingly long movie. The Shermans here contribute three great songs and a bunch of just okay ones, and their music all but vanishes from a long stretch of the second half.

Millionaire is a film that defines the concept of "bloated". An introductory number - which fades up out of a painting, the exact same gag used to start Bullwhip Griffin - is lots of fun but takes forever to get actor Tommy Steele to the actual mansion where the film will take place. There's at least five gags along the way that stop the momentum and once he gets there he dances up and down the front steps to sing his final refrain. This would be fine by itself but the entire film has this same everything-but-the-kitchen-sink mentality. Once Steele gets into the mansion, two brothers who never re-appear sing a song to demonstrate the family affinity for boxing and knock out their sister's suitor, who also never re-appears. Later, sister Cordelia has her roommate teach her how to dance in the current fashionable way in a tedious musical sequence. When Cordelia gets to the dance she hardly even uses her new moves and is swept off her feet in yet another song about dancing.

Tommy Steele, as butler John Lawless, sings and grins up a storm and steals the show, although to be fair he doesn't have too much competition. Fred MacMurray is surprisingly good here, and demonstrates a nice singing voice from time to time. Greer Garson as his wife is mostly on view to stand around and scold him; their most effective scene comes at the very end of the film and was cut from all theatrical prints. Gladys Cooper is the only real competition for Steele; her dressing down of Geraldine Paige is the highlight of the second half. MacMurray keeps alligators in his conservatory because... well, that doesn't really go anywhere either, except to provide a slapstick sequence at the 90 minute mark which, typically, goes on about ten minutes too long. Near the end there's another slapstick sequence in a bar with a terrific Shermans song, Let's Have A Drink On It, that would play better if we hadn't been beaten down to the point of apathy by two and a half hours of go-nowhere material preceding it.

The real problem is that Millionaire has no real sense of how to condense all of this into something better than its constituent parts. Details aren't just redundant, they're absurdly redundant. Even the best musical numbers are too long. Characters drift in and out randomly without any reason to be there. Each plot point is treated with about the same dramatic emphasis as everything else, as if Cordelia going off to boarding school requires the same dramatic weight as her deciding to get married.

This is a shame because what works in the movie is really good. Even MacMurray, who comes off somewhat dry in other similar roles for Disney, is unexpectedly moving when he's finally faced with an empty nest. Then, of course, he ends up going off to World War I.

Oh yes, I haven't even mentioned that the film is set between 1914 and 1917. The period atmosphere is nicely handled, with a pleasing emphasis on vintage publications like the New York Times, Saturday Evening Post, Town and Country and Harper's Bazaar. MacMuray as Biddle has extended dealings with the Marines after being kicked out of every office in Washington. He knocks out their best boxer and so the corp tolerates his efforts to teach them "self defense".

These are more scenes that do very little to advance the plot, and sadly that's about where the period detail ends. Either director Norman Tokar or cinematographer Edward Colman decided to shoot everything bright, wide, and flat, like a TV movie. It looks like every set was lit exactly once and the power switch was thrown at the start of shooting each day with no extra emphasis. It's almost impossible to tell day scenes from night scenes. Outside of a few matte paintings, there's no sense of the Biddle house as a real place. MacMurray is supposed to have a converted garage out back that he

teaches his bible/boxing classes in, but you have to watch the film a few times to understand how this connects to and relates to the house; it's just another set. When you consider the atmosphere a director like Robert Stevenson brought to even the weakest Disney movies he was handed, this is another huge demerit to this film.

Then there's the central romance between Cordelia Biddle and Angier Duke. Probably the only onscreen romance between a boxing tomboy and a jiu jitsu-tossing car enthusiast (this plot point is exceptionally weird), actors Lesie Ann Warren and John Davidson do a perfectly straightforward good job. Davidson's big ballad about Detroit, where he longs to move and become an automobile magnate, isn't very good but Davidson sells his dream well. Weirdly, the actual sequence of Davidson singing his love song to Detroit is the only one staged in the countryside - the natural trees and open sky contrasted directly with his lyrics about "a land where golden chariots are molded out of dreams". When Cordelia agrees to move with him to Detroit, the heavens open up into a menacing rainstorm. The shot proceeding it is eerily like the roadside confession in Vertigo. Is this a premonition?

The last shot of the film is an unexpected downer - Cordelia and Angie's car rolling towards a hell scape city skyline belching smoke. It's like something out of a horror movie and ends the film on an uncomfortable note - are we supposed to find this as appalling as it looks? If so, then how are we supposed to feel about this romance?

I'm sounding really down on this movie, and I shouldn't, because despite all of its problems I do like it. But it's very much a film that appears as if it could have cohered into a minor classic had there been a mediating influence like Walt Disney to iron out the problems and insist on keeping the pace up. This is almost a film that demands its own fan edit, like others have done with Star Wars.

In many ways this film seems to have been orphaned by Disney. The DVD release, in non-anamorphic widescreen, is bleary and pixellated. There are no extras to provide much needed background and context. In this form, even the visual and textual pleasure of the film are too blurred to really enjoy. As unlikely as it may be, this film would really benefit from a HD upgrade.

I didn't really expect to watch Millionaire all the way through again for this review, having seen it several times before, but once the film started unrolling I found myself watching it and enjoying it and it mostly held my attention, so despite the hundreds of words of misgivings I've typed up above, there is something to it that I find worthwhile. This one is recommended to interested parties who know what they're getting into. Ordinarily I'd say a product like this is a ruin of a great film, but that assumes that the film was ever built to completion to begin with, which it wasn't. The Happiest Millionaire is more like a pallet of lumber that's supposed to be a house. You supply the nails.

|

| The final shot - weirdly, a mirror of the opening shot of The Magnificent Ambersons |

For next week: Blackbeard's Ghost, The One and Only Genuine Original Family Band, and Never A Dull Moment