Country Bear Jamboree: The Deleted Songs

Country Bear Jamboree seems to have come into this world in very much the shape it was conceived in. As is well known, the basic idea for a singing bear band dates back to the mid-60s, when Davis was developing ideas for all sorts of musical bears - marching band bears, tuba bears, rock band bears, and more. Many of these idea ended up informing America Sings, three years later. One of Imagineering's favorite myths is the "last laugh" story, probably most famously related in the original large format hardcover "Walt Disney Imagineering" book, and this story has sometimes been used to conflate Country Bear Jamboree as some sort of extension of something Walt Disney wanted.

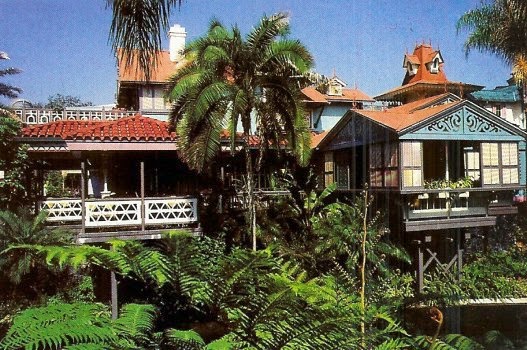

In actuality, the decision to move in the country music direction didn't come until 1969 or 1970, making Country Bear Jamboree one of WED Enterprises' first "solo voyages". Deep in the early planning files for the Florida Project is a curious Colin Campbell drawing of the Bear Band show in an open air arena-like setting, with the audience facing a huge rock wall covered with cascading waterfalls. As each act would appear, the waterfall would part, revealing a new bear. The opening waterfall gag ended up being used at the Tiki Room and the richly appointed Victorian theater we know so well was devised by Dorthea Redmond.

You probably remember this photo from Part One:

Back in 2009, the always formidable Stuff From the Park posted a larger, alternate take of the same publicity photo:

Do you see what's behind them? It's Al Bertino's original storyboard. The size of the scanned image allows us to study it in at least a little detail after some futzing in Photoshop:

As can be seen, the entire show doesn't fill a single board. Right below the "Big Albert" poster Davis and Bertino are examining, the return of Big Al to interrupt the show can be clearly seen. There just plain isn't a lot of supporting material to suggest that Bear Band was ever a radically different show.

So it was a pretty direct process to get to the show we actually know, and the various false starts along the way, for the Mineral King Resort for instance, are so deeply buried in the Archive that digging them out is not a realistic goal for this blog. But I can shed light on exactly two songs that were intended for the show and deleted.

The first of these is known simply because of a cue sheet I have listing the various numbers. This same cue sheet was used by WED in 1988 to alter to Japanese version of Country Bear Jamboree for reasons unknown, and the very fact that they had to use an outdated sheet in 1988 does tend to suggest just how little supporting documents the Bear Band show left behind.

Besides presenting an extremely different musical number order than what was used in the final show, it's full of little clues and things that were written out by 1971, for example:

Yeah, sure, for all we know "Bear Bash" is just the working title for Bear Band Serenade, but then we start coming across stuff that absolutely isn't in the show, like:

What is "The Funny Farm"? It seems to be a deleted Henry/Wendell song, as this sheet predates the casting of Bill Cole as the voice of Wendell (and Sammy, by the way).

The only song I knew of that went by "The Funny Farm" was the famous novelty song "They've Coming To Take Me Away, Ha-Haaa!" by Napoleon XIV. This would be an extremely bizarre choice for Country Bear Jamboree, although, to be fair, it wasn't any more bizarre than many of the other choices in the show itself.

"They're Coming to Take Me Away" was also a staple of a novelty record radio show based in Los Angeles hosted by Dr. Demento, which is where many people were also exposed to Homer and Jethro, so that was a possible link. As much as it tickled me to imagine Al Bertino or Marc Davis listening to Dr. Demento on their way to work, he started broadcasting in 1970, making the timing of all of this a little unlikely.

The actual solution did not present itself until I actually got ahold of the Homer and Jethro Fractured Folk Songs record ..... and there it was, right at the end of Side Two:

The Funny Farm - Homer and Jethro - Fractured Folk Songs - RCA Victor LPM-2954 1964

The fact that The Funny Farm shares the same platter with Mama Don't Whup Little Buford and Fractured Folk Song is a dead giveaway. It makes sense that the deleted Henry and Wendell song, a duo modeled on Homer and Jethro, would be itself yet another Homer and Jethro song. And this is Marc Davis territory for sure - the song is about drinking!

It isn't hard to see why this one was cut. It's hard to top Little Buford for comedy, at which point it made sense to just keep Wendell off stage until the finale of the show. A minor deletion, to be sure, but in the unstable terrain of WED Enterprises history, one worth recording.

The second number I've actually known a bit about for a long time, but never had enough information to give a full picture of what happened. It's a song from 1968 called You Make A Left and Then A Right.

You Make a Left and Then a Right - Johnny and Jonie Mosby - Make a Left and Then a Right - Capitol ST-2903 1968

Look at that hair....

Johnny and Jonie Mosby, "The Sweethearts of Country Music", perhaps typify the mainline Nashville sound better than any of the other performers this series of articles has covered. "You Make A Left and Then A Right" is a slow waltz detailing a rekindled affair.

Looking back from 2013 and knowing what we know about the way Country Bear Jamboree turned out, this song seems almost impossible to imagine in the show sung by the Sunbonnet Trio instead of "All the Guys Who Turn Me On Turn Me Down", which is who it was intended for.

I think Davis and Bertino knew they had a problem here. The song seems grossly inappropriate to be sung by three young girls. There's always been a hint of ambiguity about the ages of Bunny, Bubbles and Beulah: the songs they've always been chosen to sing aren't about fantastic kinds of romantic love, they show an awareness of attraction as a physical response. That's part of the joke, I gather: the ones in a ludicrous baby clothing know all of the reasons they want a boyfriend. A lot of the first laughs these characters get in the show is because of the disconnect between their appearance and their song.

But "Make A Left and then A Right" is a song about a fling with a married woman, which doesn't quite seem right coming out of the mouths of babes. The key line that's funny in the Sunbonnet Trio song is "turn me on", which was, as of 1971, a relatively new slang phrase. The phrase has carried on in our culture, outliving even its 60's counterculture meaning, and has an electric effect on audiences to this day. Had Make A Left been used instead, the segment would likely have seemed to be casting about for a joke. The song itself is the difference between an unrealized joke and the show stopper here.

Let's listen to the original Mosby song:

What's interesting is that despite this song seeming to be a poor fit, it seems to have quite far along in production before it was replaced. The Stonemans are listed on my song list (excerpted above) as possible voices, presumably before WED and Bruns decided to bring in three dedicated vocalists for their performance.

We also know this because Marc Davis actually painted the slides for the Illustrated Song to accompany Make A Left and Then A Right. I don't have them in very good quality - sixth generation photocopies from the back of an old information packet - but here they are, with some digital tints to make them easier to enjoy:

Okay, a few things to note about these slides.

If it seems strange to even consider a song of this type for the Sunbonnets, remember that songs like "Make a Left" were standard issue for 60's country - "Tears Will Be the Chaser For Your Wine" and "Heart, We Did All That We Could" aren't too different. "All The Guys That Turn Me On, Turn Me Down" is the only song in Country Bear Jamboree to post-date 1968. I think "Make a Left" may have been considered because it suggests possibilities for movement of the bear figures that aren't used in the final sequence - trading off lines between the three, for example, as in the Mosbys' original recording. In the final show all three Sunbonnets move more or less like mirrors of each other, encouraging audiences to focus on the Illustrated Song. The possibilities of treating each individual girl as a unique character, or even simply as lead vocalist and back up vocalists, was not explored until the Christmas and Vacation Jamboree shows.

I'd give a lot to know when the plug was pulled. Did the Stonemans also record a version of "Make a Left"? Was the idea long dead by the time they were actually in the studio? Did the difficulties in "cracking" the Sunbonnets number lead Davis and Bertino to look elsewhere, eventually finding the Stonemans and their song?

Marc and Al took that story with them when they passed on. If it exists on paper somewhere, that memo is probably long buried or long gone. What's left is just a scrap - but a very tantalizing scrap. It's an odd but very fully realized adjunct to one of the best creations of WED's golden era, tied directly to maybe the most influential single artist who ever worked in the themed design field. And looking and marveling and wondering is part of the charm, too.

Well folks, this concludes our story. So thanks for bearing with me 'till the bare end, and barrel around to see us again. Ya'll come back now, y'hear?

The Music of Country Bear Jamboree, Part One

The Music of Country Bear Jamboree, Part Two

The Music of Country Bear Jamboree, Part Three

Country Bear Jamboree seems to have come into this world in very much the shape it was conceived in. As is well known, the basic idea for a singing bear band dates back to the mid-60s, when Davis was developing ideas for all sorts of musical bears - marching band bears, tuba bears, rock band bears, and more. Many of these idea ended up informing America Sings, three years later. One of Imagineering's favorite myths is the "last laugh" story, probably most famously related in the original large format hardcover "Walt Disney Imagineering" book, and this story has sometimes been used to conflate Country Bear Jamboree as some sort of extension of something Walt Disney wanted.

In actuality, the decision to move in the country music direction didn't come until 1969 or 1970, making Country Bear Jamboree one of WED Enterprises' first "solo voyages". Deep in the early planning files for the Florida Project is a curious Colin Campbell drawing of the Bear Band show in an open air arena-like setting, with the audience facing a huge rock wall covered with cascading waterfalls. As each act would appear, the waterfall would part, revealing a new bear. The opening waterfall gag ended up being used at the Tiki Room and the richly appointed Victorian theater we know so well was devised by Dorthea Redmond.

You probably remember this photo from Part One:

Back in 2009, the always formidable Stuff From the Park posted a larger, alternate take of the same publicity photo:

Do you see what's behind them? It's Al Bertino's original storyboard. The size of the scanned image allows us to study it in at least a little detail after some futzing in Photoshop:

As can be seen, the entire show doesn't fill a single board. Right below the "Big Albert" poster Davis and Bertino are examining, the return of Big Al to interrupt the show can be clearly seen. There just plain isn't a lot of supporting material to suggest that Bear Band was ever a radically different show.

So it was a pretty direct process to get to the show we actually know, and the various false starts along the way, for the Mineral King Resort for instance, are so deeply buried in the Archive that digging them out is not a realistic goal for this blog. But I can shed light on exactly two songs that were intended for the show and deleted.

The first of these is known simply because of a cue sheet I have listing the various numbers. This same cue sheet was used by WED in 1988 to alter to Japanese version of Country Bear Jamboree for reasons unknown, and the very fact that they had to use an outdated sheet in 1988 does tend to suggest just how little supporting documents the Bear Band show left behind.

Besides presenting an extremely different musical number order than what was used in the final show, it's full of little clues and things that were written out by 1971, for example:

Yeah, sure, for all we know "Bear Bash" is just the working title for Bear Band Serenade, but then we start coming across stuff that absolutely isn't in the show, like:

What is "The Funny Farm"? It seems to be a deleted Henry/Wendell song, as this sheet predates the casting of Bill Cole as the voice of Wendell (and Sammy, by the way).

The only song I knew of that went by "The Funny Farm" was the famous novelty song "They've Coming To Take Me Away, Ha-Haaa!" by Napoleon XIV. This would be an extremely bizarre choice for Country Bear Jamboree, although, to be fair, it wasn't any more bizarre than many of the other choices in the show itself.

"They're Coming to Take Me Away" was also a staple of a novelty record radio show based in Los Angeles hosted by Dr. Demento, which is where many people were also exposed to Homer and Jethro, so that was a possible link. As much as it tickled me to imagine Al Bertino or Marc Davis listening to Dr. Demento on their way to work, he started broadcasting in 1970, making the timing of all of this a little unlikely.

The actual solution did not present itself until I actually got ahold of the Homer and Jethro Fractured Folk Songs record ..... and there it was, right at the end of Side Two:

The Funny Farm - Homer and Jethro - Fractured Folk Songs - RCA Victor LPM-2954 1964

The fact that The Funny Farm shares the same platter with Mama Don't Whup Little Buford and Fractured Folk Song is a dead giveaway. It makes sense that the deleted Henry and Wendell song, a duo modeled on Homer and Jethro, would be itself yet another Homer and Jethro song. And this is Marc Davis territory for sure - the song is about drinking!

It isn't hard to see why this one was cut. It's hard to top Little Buford for comedy, at which point it made sense to just keep Wendell off stage until the finale of the show. A minor deletion, to be sure, but in the unstable terrain of WED Enterprises history, one worth recording.

The second number I've actually known a bit about for a long time, but never had enough information to give a full picture of what happened. It's a song from 1968 called You Make A Left and Then A Right.

You Make a Left and Then a Right - Johnny and Jonie Mosby - Make a Left and Then a Right - Capitol ST-2903 1968

Look at that hair....

Johnny and Jonie Mosby, "The Sweethearts of Country Music", perhaps typify the mainline Nashville sound better than any of the other performers this series of articles has covered. "You Make A Left and Then A Right" is a slow waltz detailing a rekindled affair.

Looking back from 2013 and knowing what we know about the way Country Bear Jamboree turned out, this song seems almost impossible to imagine in the show sung by the Sunbonnet Trio instead of "All the Guys Who Turn Me On Turn Me Down", which is who it was intended for.

I think Davis and Bertino knew they had a problem here. The song seems grossly inappropriate to be sung by three young girls. There's always been a hint of ambiguity about the ages of Bunny, Bubbles and Beulah: the songs they've always been chosen to sing aren't about fantastic kinds of romantic love, they show an awareness of attraction as a physical response. That's part of the joke, I gather: the ones in a ludicrous baby clothing know all of the reasons they want a boyfriend. A lot of the first laughs these characters get in the show is because of the disconnect between their appearance and their song.

But "Make A Left and then A Right" is a song about a fling with a married woman, which doesn't quite seem right coming out of the mouths of babes. The key line that's funny in the Sunbonnet Trio song is "turn me on", which was, as of 1971, a relatively new slang phrase. The phrase has carried on in our culture, outliving even its 60's counterculture meaning, and has an electric effect on audiences to this day. Had Make A Left been used instead, the segment would likely have seemed to be casting about for a joke. The song itself is the difference between an unrealized joke and the show stopper here.

Let's listen to the original Mosby song:

What's interesting is that despite this song seeming to be a poor fit, it seems to have quite far along in production before it was replaced. The Stonemans are listed on my song list (excerpted above) as possible voices, presumably before WED and Bruns decided to bring in three dedicated vocalists for their performance.

We also know this because Marc Davis actually painted the slides for the Illustrated Song to accompany Make A Left and Then A Right. I don't have them in very good quality - sixth generation photocopies from the back of an old information packet - but here they are, with some digital tints to make them easier to enjoy:

Okay, a few things to note about these slides.

- The song itself is sung by the Sunbonnets, but it doesn't seem to actually be about them, not in any way like "All the Guys" is. The awkward, heartbreaking teenage bear in the shows' final illustrated song slides typify how many young girls feel about themselves - confused, disappointed, and surrounded by hostility. "Make a Left" doesn't even readily invite a female perspective; notice how the bear in "All the Guys" unsuccessfully dresses up to attract a mate and ends up looking like the bear in "Make a Left". To compensate, Davis has invented a guileless bachelor to star in the illustrated song, but he isn't very sympathetic.Everything above, plus the fact that the song, well, isn't in the show points towards the only real evidence we have of development trouble with the 1971 show. I doubt the issue is rights clearances - WED licensed other tracks from Capitol Records for use in Bear Band, including Blood on the Saddle. I think this was intentionally scrapped fairly far along in the process and the dynamics of the segment rethought.

- Davis and Bertino have had to change the basic song itself to make it into a joke, the only time they did this in the entire show. The Mosbys' verse ends with "...And if it's on, come on it / But if it's off, he's home again", which they have modified to "..I ain't in", which seems to imply that somebody beat the bachelor bear to the punch. The on / off light in the window makes good use of the illustrated song slide format, but the joke simply isn't very funny, and has to be telegraphed inelegantly with a huge "CLICK" cartoon bubble.

- Davis' brushstrokes are extremely rough and irregular, which could indicate rough draft status. Still, he bothered to superimpose the song lyrics over the artwork, which does suggest that these were in some degree of finality. I think the rough brush strokes suggest an attempt to revive the sometimes-crude hand-painted look of vintage magic lantern slides. The final "All the Guys" slides simplify, simplify, simplify.

If it seems strange to even consider a song of this type for the Sunbonnets, remember that songs like "Make a Left" were standard issue for 60's country - "Tears Will Be the Chaser For Your Wine" and "Heart, We Did All That We Could" aren't too different. "All The Guys That Turn Me On, Turn Me Down" is the only song in Country Bear Jamboree to post-date 1968. I think "Make a Left" may have been considered because it suggests possibilities for movement of the bear figures that aren't used in the final sequence - trading off lines between the three, for example, as in the Mosbys' original recording. In the final show all three Sunbonnets move more or less like mirrors of each other, encouraging audiences to focus on the Illustrated Song. The possibilities of treating each individual girl as a unique character, or even simply as lead vocalist and back up vocalists, was not explored until the Christmas and Vacation Jamboree shows.

I'd give a lot to know when the plug was pulled. Did the Stonemans also record a version of "Make a Left"? Was the idea long dead by the time they were actually in the studio? Did the difficulties in "cracking" the Sunbonnets number lead Davis and Bertino to look elsewhere, eventually finding the Stonemans and their song?

Marc and Al took that story with them when they passed on. If it exists on paper somewhere, that memo is probably long buried or long gone. What's left is just a scrap - but a very tantalizing scrap. It's an odd but very fully realized adjunct to one of the best creations of WED's golden era, tied directly to maybe the most influential single artist who ever worked in the themed design field. And looking and marveling and wondering is part of the charm, too.

Well folks, this concludes our story. So thanks for bearing with me 'till the bare end, and barrel around to see us again. Ya'll come back now, y'hear?

The Music of Country Bear Jamboree, Part One

The Music of Country Bear Jamboree, Part Two

The Music of Country Bear Jamboree, Part Three

+-+003.jpg)