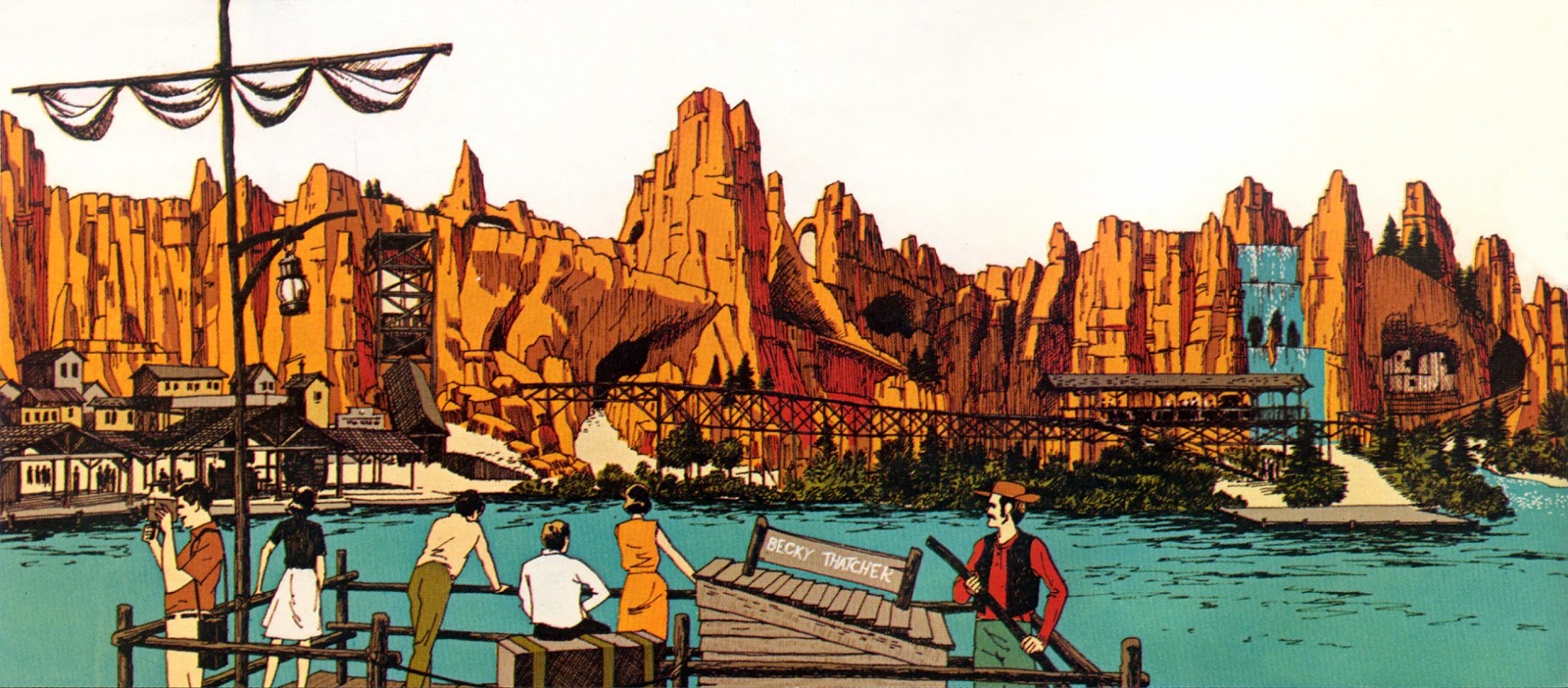

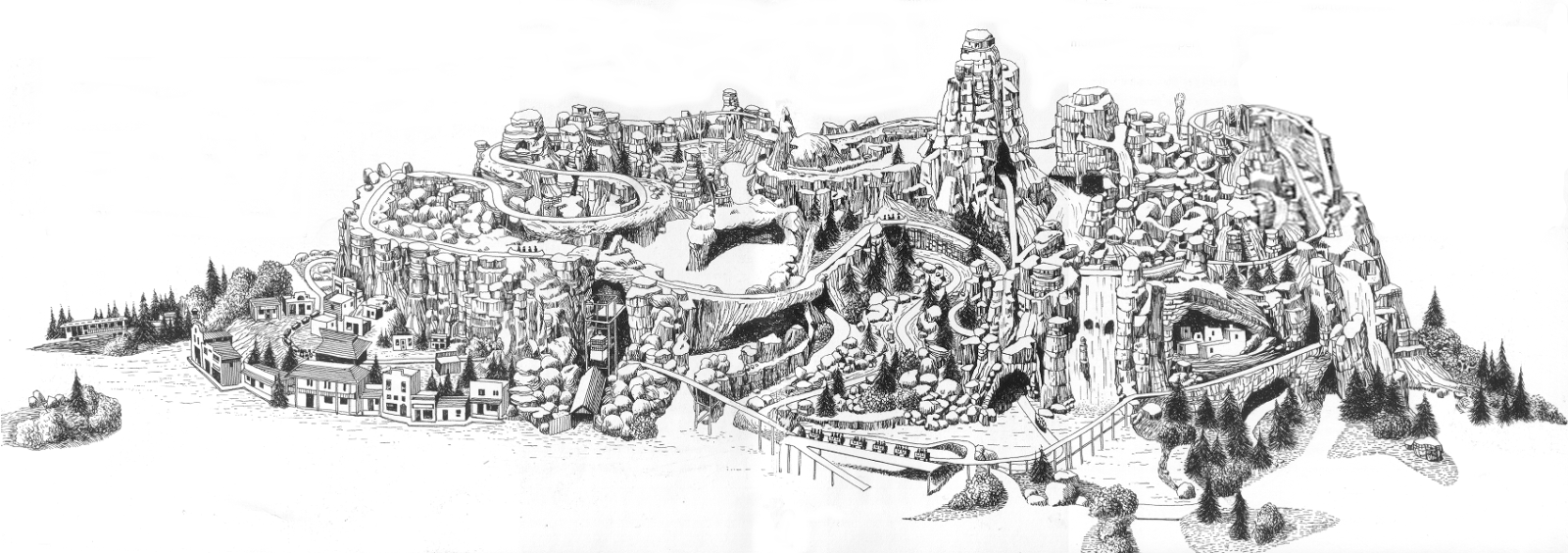

Sometimes it requires incredible amounts of devotion, of faith, and of mental stamina to be a fan.

|

| Al Huffman / DisneyFans.Com |

In retrospect, the extent of my pain and shock from that sequence of events was only fully measurable in recent years. 1998 is when Disney lost my trust and has not and probably will never regain it. There were two effects of that trip, the long term effect being a doubling down of an effort to get to Disneyland. The short term is that I fell into extreme and singular focus on The Haunted Mansion and Pirates of the Caribbean. Those two rides felt at the time like the last things I had left of my favorite thing in the world, and it was not my Disneyland trip in 2003 and move to Florida in 2003 that I began to find new things, both in Florida and California, to love.

2014 and, to some degree 2013, has been the worst year for theme park fans since the late 90s.

For the longest time it felt like we were clawing out of the abyss late Eisner left us floundering in. In 2006, 2007, and 2008 show quality throughout Walt Disney World began to rapidly improve. Unique,

|

| Al Huffman / DisneyFans.Com |

The irony is that 2014 saw the opening of two terrific new dark rides - The Seven Dwarfs Mine Train at Walt Disney World and Harry Potter and the Escape From Gringotts at Universal. By any metric, including that of this bitter old fan, this was a cause for celebration - it had been nearly 15 years since we got so much good stuff in one year in Orlando.

Problem was, the news overall was more bad than good.

Generally speaking, I'm not a rabble rousing theme park writer in the Al Lutz vein. I prefer to expend my energies writing about things I love instead of hate. Starting in 2009 and running through 2011, I began a series a "Year-End Report Cards" precisely to weigh the lasting value of additions and changes to the parks. I missed 2012, and could not bring myself to write one for 2013, when the major changes were a disastrous cut-down of Country Bear Jamboree and the endless scandal of MyMagic+'s amazingly "colorful" roll out. 2014 isn't going to happen either. If you're reading this I know you know enough reasons why.

There's times when being a blog writer you know that a response, some response, is demanded more than a simple good or bad review, yet you're helpless to affect it. What can be said of 2014's myriad scandals besides a long sigh of resignation? A blog post can be a useful tool to disseminate a viewpoint wider than, say, a forum post can, but when Disney's actively going in and ripping out stuff you genuinely care so deeply about that words cannot express your emotions, what good can a blog post - and one on a niche, niche audience site such as this - truly do? What else is there to offer besides head shaking?

Where do you define the limits of your fandom? As an adult, there's been no delayed reaction from the worst of my feelings about the past few years. After all, in 1998 Disney was merely trashing the passions a child who loved green sea serpents and believed in purple dragons and loved rides about airplanes where mannequins lurked in the background. As an adult I spend a large amount of money each year to maintain access to a place I have a lot of emotional investment in. It's an investment that embraces the whole of the place, from its start in the late 60s all the way into the foreseeable future. It's a more complex investment than I once had. Walt Disney World is now more than just Figment to me, it's a huge network of things like swan boats and utilidors and Jack Wagner background music that it was not when I was a child. It's thousands of dollars of research material, millions of words on this site, and nearly ten years of my working life.

Now, no two fans will ever be alike.

My fandom is a product of Disney, specifically the Disney of the late 80s and early 90s. This was by no means a perfect time. Eisner was ascendant, Frank Wells would shortly die, and things I loved as a child, like Dreamflight, were already suspect replacements of what was there originally. But I am a product of Disney of that era, and this was an era when Disney was still a company hungry for validation. They had not yet absorbed ABC and ESPN, to say nothing of Go.com, Video.com, Pixar, Marvel, and Lucasfilm. They told me to hold them to the absolute highest standard, and you know what? They came through to me. Consistently. I came of age when one animated classic after another poured out of Burbank, when EPCOT Center was still fairly new, then Disney-MGM Studios changed more in a year than it has in the past decade.

I saw old WDW at the very end of the time when it existed, and I saw it repeatedly. I was in the position to be confused when 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea closed, to mourn the removal of Main Street's beautiful Flower Market, to be crushed by the closure of Journey Into Imagination and many other of my favorite rides.

I saw old WDW at the very end of the time when it existed, and I saw it repeatedly. I was in the position to be confused when 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea closed, to mourn the removal of Main Street's beautiful Flower Market, to be crushed by the closure of Journey Into Imagination and many other of my favorite rides.I was, in short, extremely lucky to be able to travel to WDW every other year for about a decade. I saw it a lot. I probably should've wanted to go somewhere else, but I didn't. I saw it enough to get bored of it, but I didn't. My appreciation deepened. Then the late 90s hit.

If you consider how much changed at Walt Disney World between 1989 and 1999, and then how little has changed between 1999 and now, is it any wonder that the gap between the old school fans and those who began visiting in, say, 2002 is so monumental? It's inevitable. It's sad, but it's what's happened.

This is why it kills me to see the old school fans and the new fans going at it with hammer and tongs over and over and over again on the internet. I'm a product of a company which is now almost totally unrecognizable, and my Walt Disney World is long gone. But I'm nothing but an earlier version of those new school fans who go out of their way to find new reasons to insult and dismiss me.

It's not that I hate current Walt Disney World, but it's no longer my Walt Disney World, and human emotions all being equal I'm going to by definition feel conflicted about it. These criticism don't come out of some desire to "take Disney down a peg" or piss all over your 2013 vacation. I'm upset because I'm genuinely, emotionally, deeply dismayed by these things. I don't require agreement, but empathy would be nice.

I didn't set out here to complain; I want to teach. But the deadening impact of the walls raised between individuals on the internet creates, I fear, fans who see other fans of such a different Disney culture and Disney background that they assume there can be no overlap between them. But I'm a fan too, and I love my stuff just as much as other, newer fans. I just like different stuff. There's no crime in that.

Which is why I've tried a new approach here. Instead of taking the scholarly, remote approach most Disney fans take when trying to discuss these things, I'm going to make it totally, grossly, entirely personal. If you've read this blog enough you probably know my positions, but I feel some take little time to consider why they are that way. I didn't tumble out of the womb disappointed in a stale state of Future World. It took a long time for that love to curdle into disappointment, and finally apathy. I can't pretend to tell the whole story here, but I'll try to give some insight not into what the passing of these things means not to Disney, but to me.

I did not have a "crisis of faith" in 2014 because my experiences in the 90s told me to expect the worst to begin with. But I'm also too entrenched now to entirely stop caring. Yes, it's harder and harder for me to enjoy a lot of stuff I once did, but it's not as if I don't enjoy myself as fully as possible when I do commit to go there. But unlike when I was a vacationer, that commitment now comes bound in with an ideology. I'm enough of a fan to keep caring and too much of a fan to accept lousy choices.

One reason 2014 hit me hard is because each of the three major disasters has struck a different pillar by which I hold the Disney theme parks to be superior popular art, the thing that makes them better than a Six Flags. That's different for each visitor but for me much of the appeal of the places comes down to three poles: excellent design, historical legacy, and conceptual integrity. That's how I define my fandom.

It's Just Stairs

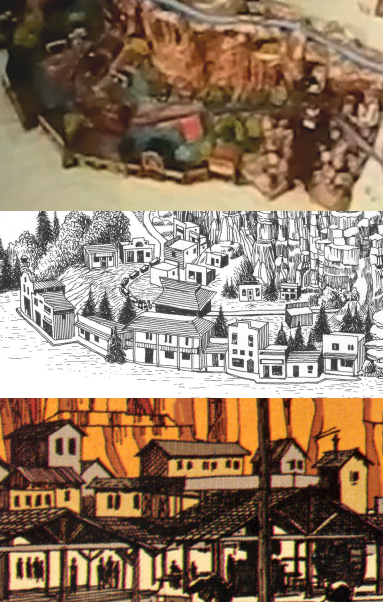

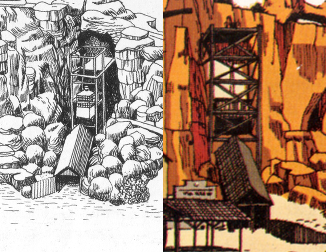

My first and largest disappointment this year was the design disaster, New Orleans Square.

Now, to be abundantly clear, New Orleans Square is sacred territory for this writer. You are reading this site right now as a direct result of that area. By 2003, my mind was opening to the idea that there was more to these theme parks than I was aware of thanks to writing my Mike Lee and others, but New Orleans Square at Disneyland twisted my head off and put it back on my body differently. It was a life altering event.

Besides the staggering greatness of the West Coast Pirates of the Caribbean and the intimate, quirky original Haunted Mansion, New Orleans Square was epochal. The intimate courtyards had not yet became crowded with sales items and The Disney Gallery was where I bought my first issue of The E Ticket and began to take Disney History very seriously. New Orleans Square was quiet, understated, and perfect. Upon the closure of the Court of Angels in 2013, irritated brand loyalists came out of the woodwork and claimed that the feature was worthless because they themselves had never gone back there, which was of course precisely the point.

Loud tourists, crazed Fastpassers and people whose entire kitchen is Mickey Mouse themed blew past the area daily because to them there was nothing especially "Disney" about an intimate courtyard. What upset aesthetes like me is that, conversely, there was nothing more Disney than the Court of Angels -- Walt Disney, that is. Walt built things because he liked them and trusted his instincts enough to trust that the public would too, and more often than not he was right. The Court of Angels was the symbol of the entire Disney way of doing things, the thing that made Disneyland different than a boardwalk. It was there because it was nice, and simply being nice was more than enough.

The courtyard closed in 2013 to make way for an expanded Club 33 lobby, but that wasn't the worst of it. Club 33, an ageing private club that was probably no longer a secret worth keeping, had changed numerous times since it opened following Walt's passing but had remained strictly faithful to the interior decor of the original WED team and, presumably, Walt's own wishes.

All of this would change with laudable aims of improving the floor plan, access and food of the club. Now, I've never been to Club 33 and certainly now will never want to because the main appeal of the place to me was just that it was so traditional, but really what upset me is not that Club 33 as we knew it was stripped out and replaced with something that looks a lot like a cruise ship interior, it's what these changes meant to the exterior of the buildings which contained the club.

|

| Left: 1966 (Daveland) / Right: 2014 (Andy Castro) |

Frankly, it's hard not to see what they did and wonder if they could've produced a poorer effort. Gigantic windows ruin Walt's carefully crafted forced perspective. New features are placed in ways which destroy sightlines and symmetry. As Herb Ryman once appropriately put it, "Bad taste costs no less."

|

| Top: 1966 (Daveland) / Bottom: 2014 (Andy Castro) |

This came at the tail end of eight years of compromise and homogenization. I never got to Disneyland in time to see weird little things like The One-Of-A-Kind Shop or Le Gourmet, but the sort of thinking that slaps Jack Skellington on a sign and calls it a day has totally taken over. In 2006, the beautiful Royal Courtyard, my favorite, became overflow Pirate merchandise. At that time, a tarp was strung up over the courtyard, blocking views of the architecture above and the doors into the courtyard from the street were locked, forcing traffic to proceed directly from one shop to the next. All of this effectively removed the Royal Courtyard.

|

| Court of Angels in the 1980 Annual Report |

Court of Angels was the last to remain standing, but the end was foretold. Periodically converted to sell merchandise, it finally went the way of its peers. In Bob Iger's New Orleans Square, intimacy and charm only came after merchandise and dining sales.

This is the fate of the last area overseen by Walt Disney, the design pinnacle of Disneyland. This was the best area of the defining theme park of the world.

2014 was the year I lost faith in Disneyland. Walt's park had been through rough stewardship in previous times, and of course nothing is ever perfect, but when they say you can never go home again things like New Orleans Square's through trashing is what they mean. My favorite and the defining area of any modern theme park had finally, at last, been compromised. The quiet courtyards and intimate details, but more than that, the staggering scope of the accomplishment represented by that north-south stretch of riverfront property from Pirates of the Caribbean to the Haunted Mansion is something I can only relive in memories.

And now I must find a new favorite theme park area. Somehow.

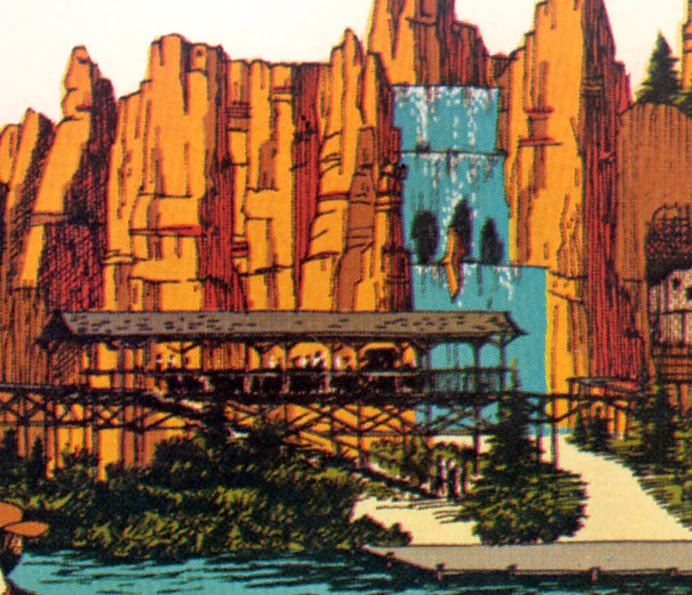

It's Just Waterfalls

The second disaster was admittedly less significant but struck me through the heart just as strongly, and that was the removal of the Polynesian Village's lobby waterfall centerpiece.

Now, I was at the Polynesian just last week and many of the upgrades I've been seeing around the hotel have been excellent and badly needed. Beautiful volcanic rockwork has sprung up where previously suspect wallpaper and drywall was the norm. The cartoonish volcano pool is being rethought, and even the old name "Polynesian Village" has been restored. Everything about the project seem to be an effort to update but retain the Polynesian's funky retro charm.

And, it must be said, it's not like the Polynesian hasn't successfully reinvented itself before. In the 70s it was a paradise of turquoise and sea-green tiles, wicker chairs, and goofily "modern" design touches, more Vegas than the hotel many know. In the 90s it was turned into the orange-and-earth tones garden it remained until this year. So it's not like the Polynesian has ever been just one thing, unchanging. It's a modern and wildly popular hotel and it has been and will be continued to be upgraded because that's what hotels are.

|

| Davelandweb.Com |

I'm saying all this as a preface because I have been attacked and probably will be again for being a stodgy traditionalist who would have all of Walt Disney World unchanged, which is presumptuous guff. But I do believe that we can retain the best elements of the past and combine them with needed refreshments and upgrades to produce a product which is both always relevant and timeless.

The Polynesian waterfalls were the heart of the resort. They were the signature central moment of the resort, as important to its impact as entering Wilderness Lodge through that tiny antechamber and stepping into the golden glow of that lobby. The hiss of the automatic doors and entering a space both interior and exterior, the sound of the rushing water over the rocks, and the dapple Florida sunlight on the interior garden was the defining, unique statement of that hotel.

In the years following its opening indoor/outdoor gardens with waterfalls became a feature of many a hotel around the country, so, yes, it's not that the Polynesian by 2014 was unprecedented and unique. Yet that same logic would have us demolishing Pirates of the Caribbean because it spread the popularity of pirate-themed rides throughout the world. The Polynesian waterfalls were amongst the first and best example of this particular lobby scheme. They were not too tall to become annoying, and the lobby was not too large to lose its sense of vintage intimacy. Entering the Polynesian was like being embraced by the arms of the tropics.

This to me was the legacy item that was destroyed. Yes, it may yet be conceivable to have an attractive Polynesian Village without the falls but there is no getting around the fact that a large chunk of Walt Disney World history has gone off to the trash heap.

I've heard various reports about how "the falls could not be saved" and differing estimates about mold, and asbestos, but this one was all about money, and the proof in the pudding is that the beautiful original waterfalls have been rebuilt as a teeny tiny little mole hill of a waterfall complex. Interior running water is interior running water. Why would Walt Disney World risk the apparent mold infestation we're told the falls were demolished to get rid of? I've used the Polynesian as a general base of operations and hangout since I moved to Florida in 2003, and I can tell you from personal experience that starting in 2006, the waterfall itself would be off about 25% of the time. I've seen Disney turn off, gut, and refurbish those falls and the ones outside three or four times in ten years. It was self-evident that the waterfall system was badly in need of a solution.

Which is why the falls should not have been demolished, but totally rebuilt. They didn't even need to keep that exactparticular waterfall arrangement from 1971, but the garden and the falls in some arrangement should have been retained, because that lobby is the signature element of the resort, and removing it is no less significant than if, say, the monorail was rerouted to go around the Contemporary or if the Grand Floridian's lobby were filled in with DVC units. I can hear the internet now: "You don't understand, the Grand Floridian lobby could not be saved! People forget that Disney is a business."

There's that money claim again, and guess what? It's still the core of my objection. When I look at that little pile of pebbles in the center of the Polynesian I see not a dramatic, modern reimagining but a cheap, lousy replacement. I refuse to accept that the same creative team that restored the original name and typeface to the hotel would also have considered removing the signature visual element of the place to be an attractive option. And since the decision was creatively compromised and certainly wasn't operationally justifiable, that leaves us the last option: budget.

The modern reality of Walt Disney World is that the resort continues to report record profits and attendance year after year, but they cannot be bothered to throw enough money at one of their signature hotels to get a job done properly. What percentage of a stock point would rebuilding the waterfalls actually effect? How many rooms need to be filled for a reconstruction to pay for itself?

And we're not talking about just any hotel here - we're talking about the hotel that's asking, at its cheapest, around $500 a room a night, and more often around $800.

To take this number out of the squirrelly, complex, fluctuating-discount-ridden monetary minefield of Walt Disney World and put it in real world terms, I looked up 25 top hotels in the country, and overall found that their average asking price topped out around $300 a night. For the price of one night in the funky Polynesian I could stay two nights at the Waldorf-Astoria on Park Avenue in New York. Prices for Four Seasons hotels in places like Atlanta and Colorado came nearer to the Walt Disney World price range, but the only the mega hotels in the tourist section of Hawaii matched or exceeded the sticker value Disney places on their hotels. And for your money you're not getting a Waldorf-Astoria, you're getting a Disney hotel where the restaurants serve chicken tenders and the lobby is filled with shrieking children.

So let's forget for a moment about Disney, or Disney history, or Walt Disney World, or DVC, about all this nonsense political stuff we get caught up in as Disney nerds. We're talking about a hotel that is pricing itself amongst and often above the finest hotels in the country that still couldn't justify properly and respectfully replacing its signature visual element. This is an embarrassment.

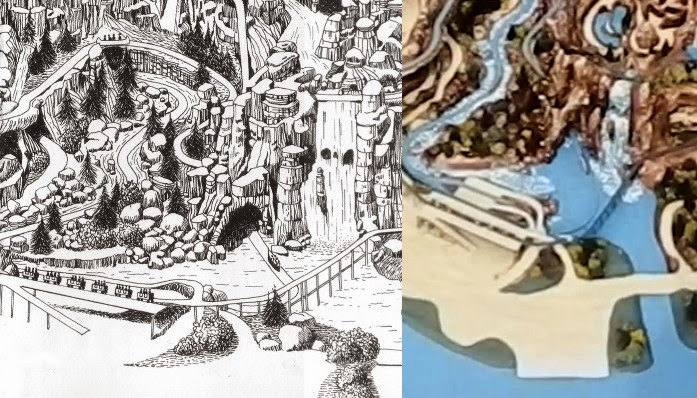

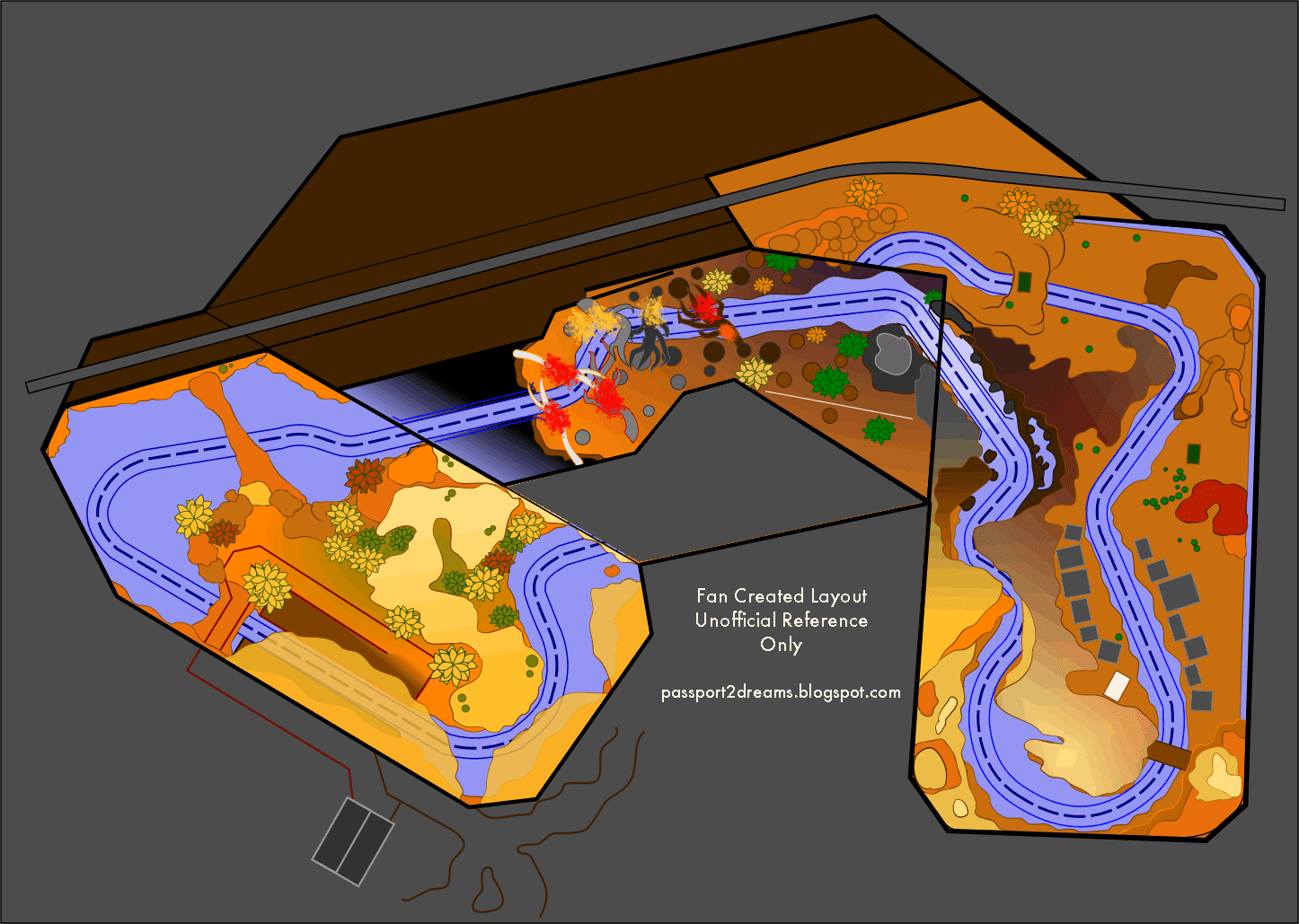

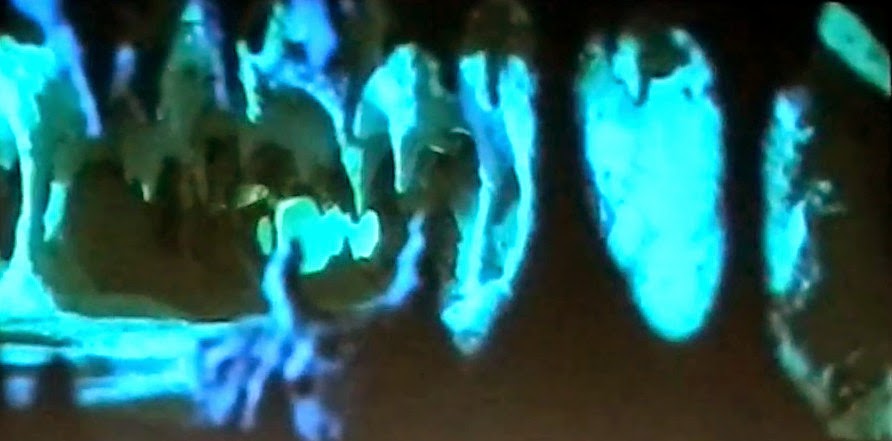

It's Just a Boat Ride

Yeah, you all knew this was coming because we're still smarting from it. It must be said: I never outright loved Maelstrom. I actually liked the Spirit of Norway film at the end more than anything in the ride. But I'm not everybody. I know those younger than I who missed out on World of Motion or Journey into Imagination or Horizons who wept the day its closure was announced.

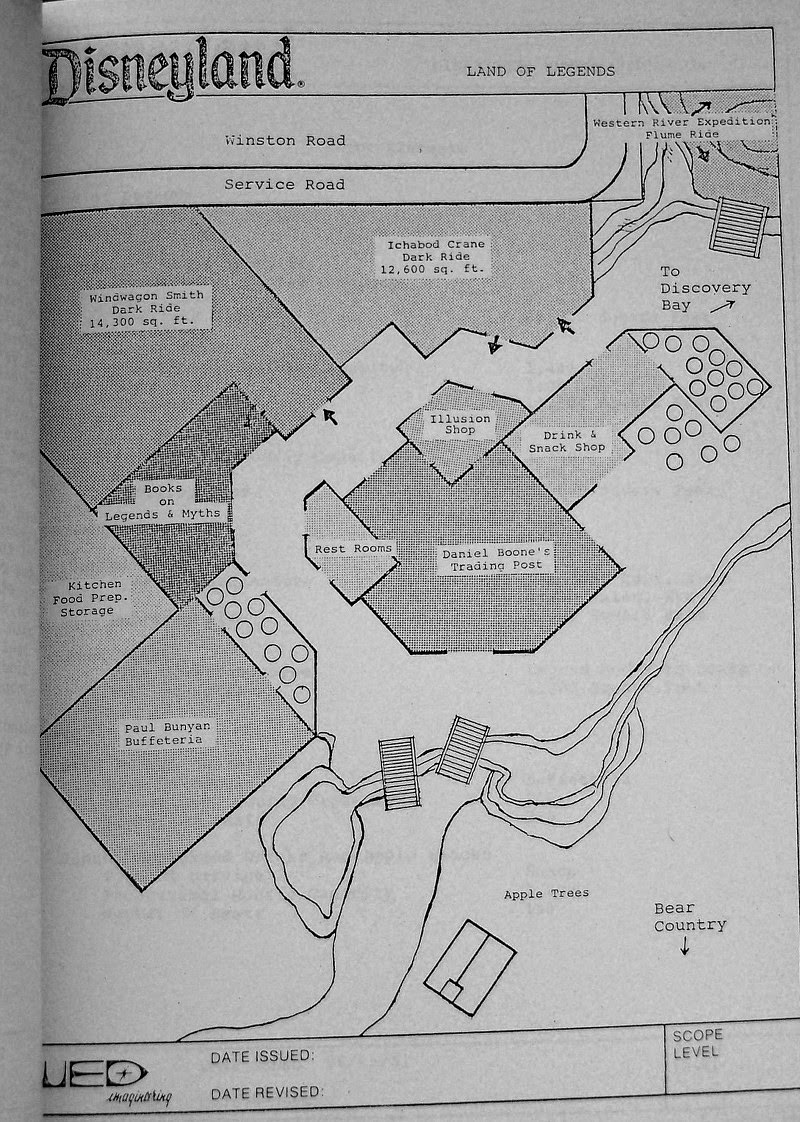

At this point in most other articles about Frozen in Norway go on to describe the pros and cons of Frozen, its popularity, the decision, the fan reaction, but you know what? I don't have to. You've all read those before, and besides, most authors want to reframe their argument to be specifically about Frozen ("The kids love it!") or specifically about Maelstrom ("EPCOT Center!"), but that's all just a distraction from the core of the apple here, which is that Epcot, thematically, is a joke. The Frozenification of Maelstrom was just the drop that caused the vase to overflow and it's been coming for twenty years now. Epcot is the conceptual integrity disaster of the year, and in a way it's the biggest one, because this isn't just one area of a park or a hotel but it's an entire theme park.

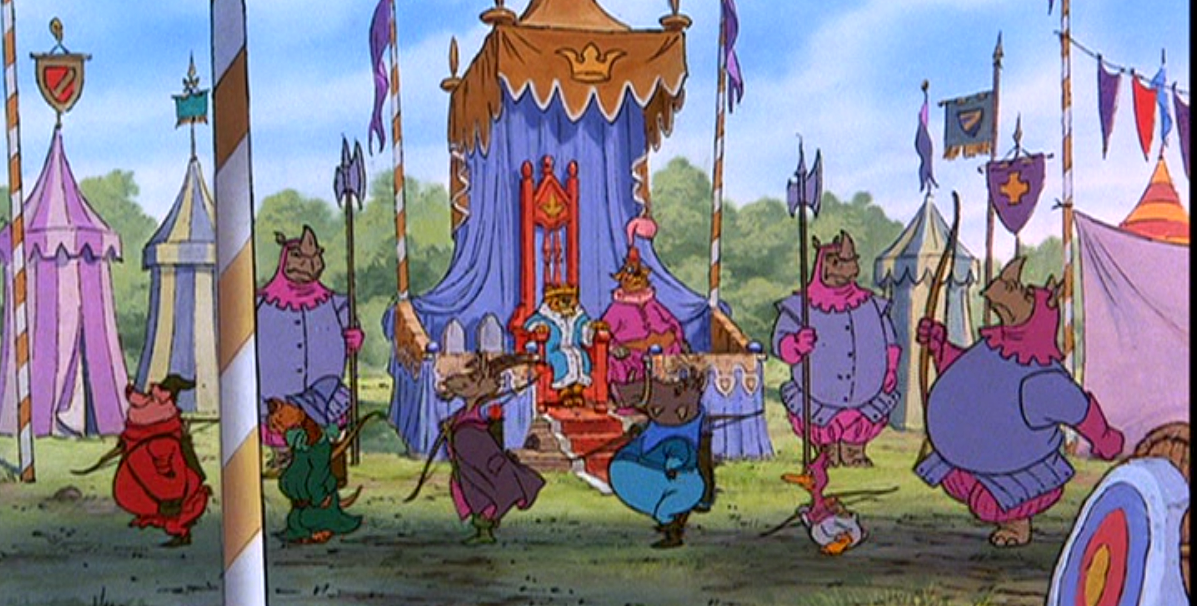

|

| hintofspy |

We're talking about a park here which closed and gutted all of its wonderfully designed family favorite attractions. Honestly, most of them were around for mere blips on its lifetime and so never quite hit that multi-generational quota that graduates attractions from being merely good to being classics. There's nothing to compare it to because no Disney theme park in history has ever so thoroughly massacred its own core content. Imagine if Magic Kingdom, tomorrow, demolished Pirates of the Caribbean, Jungle Cruise, Big Thunder Mountain, Haunted Mansion, It's a Small World, and Space Mountain. That's what happened to EPCOT.

Those of us who loved EPCOT kept going out of either obligation or grim determination that somehow, someday, things would get better. We began to spend more time in World Showcase and things which were once kinda lousy attractions in a park that also had Horizons, like the O Canada film, became treasured heirlooms. We began to skip through Future World and believe that World Showcase was Epcot still. It became a hiding place. From far enough away Test Track does indeed still look like World of Motion. And we were kidding ourselves.

The removal of Maelstrom is not significant on its own so much as it's the final nail in the coffin. People are finally starting to deal with their denial and the locus of the problem is Maelstrom but it's not the be all and end all. Listen: there's nothing inherently sacrosanct about, say, Magic Journeys. It's not like World of Motion was a perfect, unsurpassed achievement. What we were kidding ourselves about, and what Disney screwed the pooch on spectacularly, is that Epcot was in any way relevant and meaningful anymore, that it had become anything but a random collection of stuff.

Myself, I stopped attending. The same author who wrote "An EPCOT Generation Manifesto" cannot be bothered to enter the park anymore because I cannot see the point. There's very little there for me to enjoy. I can count it on one hand: Living with the Land, Captain EO, Impressions de France, American Adventure and Spaceship Earth.

Of those, only Impressions de France has dated gracefully. Living with the Land is passing out information about agriculture that's twenty years behind the times in a pavilion so ludicrously out of date you can't even find a discussion of the word "organic" anywhere in it. A trip to your local Whole Foods is more informative. Captain EO is... Captain EO. American Adventure is an earnest but patchy show and Spaceship Earth is a similar mix of dreadful and sublime.

I'm done kidding myself. For the foreseeable future, at least, Epcot is not going to get better, not while it's still outperforming half of the parks at Walt Disney World, not while it still runs food festivals that jam the park and destroy the atmosphere, not while it makes a mint each day selling alcohol from outdoor kiosks to temporarily morally liberated tourists. Visiting Epcot, to me, is like visiting somebody you admired once who hasn't done a thing in twenty years and reeks of expensive tequila.

|

| ChrystinaNoel.com |

I will say this: I do not believe that Epcot is beyond help, but it is beyond my ability to foresee it. Disney has no more interest in addressing audiences intelligently than they do of demanding better from themselves. My experience is that people act as intelligently as you treat them, but almost everything at Epcot is keyed to the most facile understanding of its audience. People see outdated data presented condescendingly and blow it off, then the referees on the sidelines shriek triumphantly: "You see? Nobody goes on vacation to learn!". Meanwhile, very far away, museums and cultural exhibits enjoy a new renaissance.

The tragedy of it is that we are living in the most literate, most informed American society ever, thanks to the rise of the internet and the democratization of knowledge, and Epcot has refused to keep up. It's not even trying. The classroom is empty and there's no office hours because it's off water skiing with Guy Fieri. It's slacking, and Disney has no reason to wake the sleeping babe. A walk through Epcot is like seeing the Rosetta stone handed to an infant. She shakes it, she breaks it, then she asks for an Elsa dress - everyone must have one.

Never Been Better

I still get a lot out of Disney theme parks, which is why I still go. They recharge me creatively, improve my attitude, and surround me with beautiful sights. There's value in that, but the gulf between the experience of being there and the experience of expressing an opinion of being there online could not be greater.

I emerged on the other side of 2014 feeling like a cartoon character after a bomb goes off and everyone's all covered in soot. Having been through the worst of the 90s, I was still not prepared for things to get quite so bad. The Disney Internet, meanwhile, has been at peak toxicity for over a year running. The amount of screaming is very high and the amount of useful discourse is very very low. If you can't go online to mourn with your fellow fans without being abused and attacked, where is there to go? The shrieking in certain quarters, meanwhile, has become so loud and fevered to resemble either desperation or censure. Some Walt Disney World fans it seems would rather shout you down that understand you, as if all fans are created equal or as if likes and dislikes aren't some intensely personal particular reaction.

This essay is intended as a memorial. Perhaps in the future I'll look back and feel much differently but this essay is about how I feel exactly at this moment. 2014 was a singular year, and although I am not defeated - contrary to one common lazy response intended to shut down dissent, I no more wish to stop going to Disney theme parks than they do - I am burned out.

It's not as if there have not been positive rumblings on the horizon. Disney-MGM, in particular, may finally attempt to live up to its potential, and the overall maintenance quality and aesthetic quality of everything - no matter how old or how suspect - has been very high. Yet my heart is heavy. It seems the mere fact of trying to be a fan these days is more Under New Management and less It's A Small World.

I'm burned out because this year has reminded me of the reason I had to quit Disney as a Cast Member to begin with: for all the money, all the time, all of the energy expended on showing your love to a place and a product, Disney does not love me back. These words are just a scream into the abyss among millions, and the internet is an echo chamber.

In 2015 let us try to be sympathetic to our fellow fans. I don't like the Sorcerer's Hat at the end of the street at MGM but I sympathize with those who will mourn it's removal, because they have never known the park without it. And while I do trust that, much like when the Wand over Spaceship Earth came down, some will eventually grow to like the restored view, I still think back. I still think back to that child who loved Delta Dreamflight and was hurt to learn that those who loved If You Had Wings hated it.

Listen, there's no moral relativism when it comes to liking or disliking weird, stupid shit. There's rides I love that will never be a post on Passport to Dreams because I think they're indefensible - Revenge of the Mummy, for example. That does not affect why I love them. As I grow older I'm more comfortable with that. But those of us who grew up with World of Motion should maybe stop feeling superior to those who grew up with Test Tack, as if our childhoods were objectively superior to theirs. They have their reasons, and I have mine.

|

| Disneyland did Frozen right (Andy Castro) |

In 2015 let's all try expecting the good but stop ignoring the bad. The fact is that Magic Kingdom is in terrific shape, help is on the way for MGM, Animal Kingdom will shortly be far more complete than it ever was, Disneyland is doing fine overall, California Adventure is still a mixed bag, and both economic and cultural forces are aligned against Epcot for the moment. Perhaps her day may come again, perhaps it may not.

Those are my realistic suggestions. My unrealistic suggestion is that in 2015 let us expect more from Disney. Those people who fill up social media with bile are right: Disney is a business, not a fairy in a garden or an invisible bridge across a chasm. I shouldn't need to #HaveFaith as they make poor decision after poor decision.

I don't work that way. I don't think I owe Disney a thing. I'm their customer, not their servant. I'm paying to help keep the lights on. Okay, maybe just one light in the grand scheme of things, but what of it? Do I need to keep a running spreadsheet of my Disney expenses to be worthy of their interest? This is a premium product and there is no shame in expecting a premium result.

I want to see good projects being led by talented people that expand Walt Disney World without closing other parts of it.

|

| WDW Shutterbug |

Moreover, I want a reason to believe again. It's been a long time since I expected anything good to come rolling out of Burbank. Based on what I see on Twitter and elsewhere, we are all ready for a change. Disney has finally fallen victim to the malaise that's stricken Hollywood since the late 90s: a total lack of conviction. Nobody inside the company seems to be making anything they believe in anymore. Some things slip through the cracks here and there, but I want to see passion projects, not spreadsheet low-risk investments. Disney controls the most remarkable creative staff in the industry and they set them to work toiling out things like Cars Land: beautifully done, emotionally hollow. Is it any wonder so many Imagineers are jumping ship to Universal Creative?

I haven't got a reason to have faith anymore. And me, and many others, I think, could really use one right about now.

Passport to Dreams Old & New Year End Essays

My California Adventure (2013)

Notes on a Time That Was Not Happy (2014)